The Tsar’s French Helmet, the Imperial Russian Adrian

An Experiment on the Northern Front

As the Great War raged across Europe in the winter of 1916, a steamship named St. Peter docked at Arkhangelsk, a northern sub-arctic port town in the Russian Empire. The ship had come from Brest, France and carried in it’s hold 15,000 French steel helmets. These helmets were part of an experiment, destined for the Russia’s Imperial army. Like all armies on both sides of the Great War, Russia was losing an unacceptable number of men due to head wounds. Something needed to be done. Unfortunately while the other armies in Europe had already began developing their own steel helmets, Russia had not. Russian Military Officials though had taken note of the effectiveness of the new steel helmets being used by their French Allies and sought to procure a small number of these French helmets for an experimental field trial. An order was issued by the Chief of Staff of the high command on October 22, 1915 to purchase 15,000 French helmets. The order was passed to A. Ignatiev, the Russian military agent in French who negotiated the sale of the helmets from the French quartermaster for 75,000 francs. On November 10, 1915 the Main Directorate of the General Staff issued a communique to the Imperial Armies Main Quartermaster’s Department that one division of the regular army was to be equipped with French helmets on a trial basis.

The French steel helmets were known colloquially as Adrians so called for it’s developer Colonel Louis Auguste Adrian. Colonel Adrian had been struck with the idea for a protective steel helmets after a conversation with a wounded French soldier who had survived an almost certain fatal shrapnel wound by placing a cooking pot lid under his wool cap. From that conversation the Colonel would go on to design the French army’s first steel helmet, one that would dramatically reduce head wounds and saved countless lives.

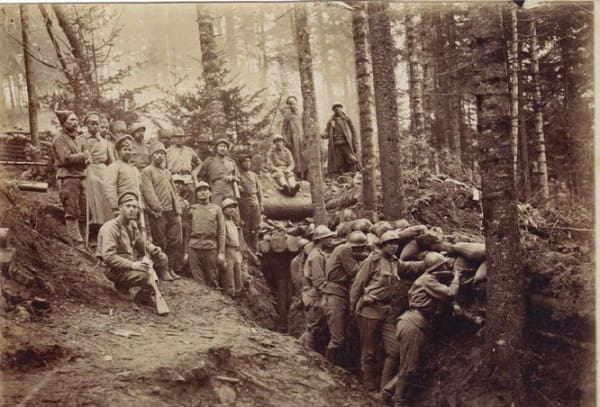

After arriving in Russia, the Adrian helmets were sent by rail to Rezhitsa in modern day Latvia where they were received by the Northern Front’s quartermaster. By July of 1916 the helmets were finally distributed to Russian soldiers in the field and the experiment began. The first to receive them were members of the 5th Army.

The helmet received by the Northern Front quartermaster were no different from the version worn by French Soldiers. The helmets were painted Horizon blue which matched the French combat uniform but would clash with the khaki uniforms worn by the Imperial Russian Army. There was one small difference, at the request of A. Ignatiev, that the helmets were not fit with French insignia on the front.

Even before the helmets were issued to the first of the Russian troops, the helmets were already receiving criticism. Despite a French study which showed that wearing of a steel helmet eliminated three quarters of all head wounds, on March 12, 1916 the Chief of Staff of the High Command issued a resolution against their use. The Tsar himself had ruled against the use of steel helmets by the Imperial army believing it would diminish the soldiers martial appearance. Due to the Tsars intervention, the purchase of further helmets was stopped.

The Tsar’s Reversal

Despite the Tsar’s intransigent on the use of a steel helmet by his armies, other members of the Russian government were not willing to let the idea die. During the spring and summer of 1916, members of the Russian State Duma as well as the Special Council for State Defense visited the other Allied states of Belgium, Great Britain, France, and Italy to discuss effectiveness of the steel helmets their nations wore. Most of these nations had been wearing steel helmets for over a year and had thoroughly documented their safety record. The council was impressed with the findings and decided to petition the Chief of Staff to the Commander-and-Chief M.V. Alekseyev to recommend the Russian Army be equipped with steel helmets. The council also appealed to the Tsar directly to change his previous decision to let the army be equipped with steel helmets. The extra effort by those advocating the use of steel helmets was not wasted. After considerable argument, the Tsar reversed his decision and allowed for the purchase of steel helmets from the French to move forward.

With permission from the Tsar granted, Alekseyev wrote to War Minister D.S. Shuvaev requesting the immediate purchasing of 2 million Adrian helmets. As a sign of the urgency for the situation, perhaps with the fear the Tsar might resend his permission, Alekseyev requested that the purchase move forward without waiting for the results of field trails being conduction by the 5th army. The purchase order was again forwarded to A. Ignatiev, Russia’s military agent in French who negotiated an agreement with France for the purchase of the 2 million helmets. Under the agreement, the first 250,000 helmets were painted horizon blue and were fitted with the French RF (République française) frontal insignia. It was agreed that these helmets would be shipped on the first available freighter. While the subsequent helmets were shipped in 18-20 thousand lots with the expectation that they would arrive in Russian before the end of the shipping season. The first lot of helmets were receive in early October, 1916. It appears that no times was wasted issuing them out to the troops as the Darnitski depot. Kiev reported taking delivery of 146,000 helmets October 19, 1916.

Supply Chain Issues

Two million helmets would not be enough to equip the Russian army and by September 22, 1916 Commander-and-Chief M.V. Alekseyev proposed that another 1.5 million Adrian helmets be purchased from France. The shipping of helmets from France to Russia proved to be problematic because Russia’s ice choked port facilities which made deliveries problematic during winter and early spring. Aside from natural elements, German U-boats prowled the northern shipping lanes. Three freighters carrying a combined total of 160,000 helmets were sunk by German U-boats in 1916 and 1917. Unfortunately, even after the helmets were delivered, there were other problems. On January 12, 1917, an accidental ammunition explosion at the port of Romanov-on-Murman destroyed a large delivery of Adrian helmets. Those helmets that did arrive were sent by rail to various supply depots and they were issued out to front line units. This process was slow and could take weeks.

Another 180,000 helmets destined for Russia stayed in the French port of Brest, undelivered due to the out break of the Bolshevik Revolution. The last ship carrying Adrian helmets from France left Brest in September of 1917. All told 1,977,000 Adrian helmets would be shipped from the France to Russia. Despite the seemingly large number of helmets that were shipped, it simply wasn’t sufficient to equip the vast Imperial Russian Army.

The number of these helmets distributed by Russian quartermasters to soldiers in the filed can only be guest at. Original photos of some Russian units give the indication that most men of that unit received a helmet. This is the exception though. More commonly photo of front line units give the impression that only a few men were fortunate enough to receive a steel helmet. With helmets in short supply, it would make sense that an attempt was made to distribute helmets to front line units where they were needed most. Even by late 1917 after most of the Adrian helmets had been delivered most photos of Russian units show only small numbers of helmets being worn.

Horizon Blue and Khaki

For those Russian soldiers who were fortunate enough to receive an Adrian helmet it was painted either Horizon blue or khaki. The French had painted their helmets horizon blue since they were first issued in late 1915. The color was used simply because it matched the French uniform at the time. A. Ignatiev was certainly aware of this fact, and likely preferred that the helmet be painted a color to match the khaki-olive color of the Russian army’s uniform. Due to the urgency in which helmets were needed, there was no time to wait for them to be repainted. Attesting to that urgency, A. Ignatius petitioned General Joffre, Commander and Chief of all French forces, that the first consignment of helmets be withdrawn directly from French reserves. Those first helmets were shipped to Russia painted horizon blue and were subsequently issued to Russian troops in that color despite not matching the uniform.

Starting in mid 1916 the French ordered a change in the color of the uniforms worn by their colonial troops from horizon blue to a olive-khaki color called moutarde. The subsequent change in uniform necessitated that helmets issued to colonial units be painted the moutarde color to match the uniforms, and helmet factories started to stock the moutarde paint. This new color was a close match the khaki-olive uniforms the Russian army was wearing. It should be noted the color moutarde ranged in shades from yellow-brown to a darker olive depending on which of the eight different factories manufactured the helmet. After the first delivery of the 250,000 helmets, the moutarde color became available, and at the request of A. Ignatiev all subsequent deliveries of Adrian helmets destine for Russia were painted moutarde.

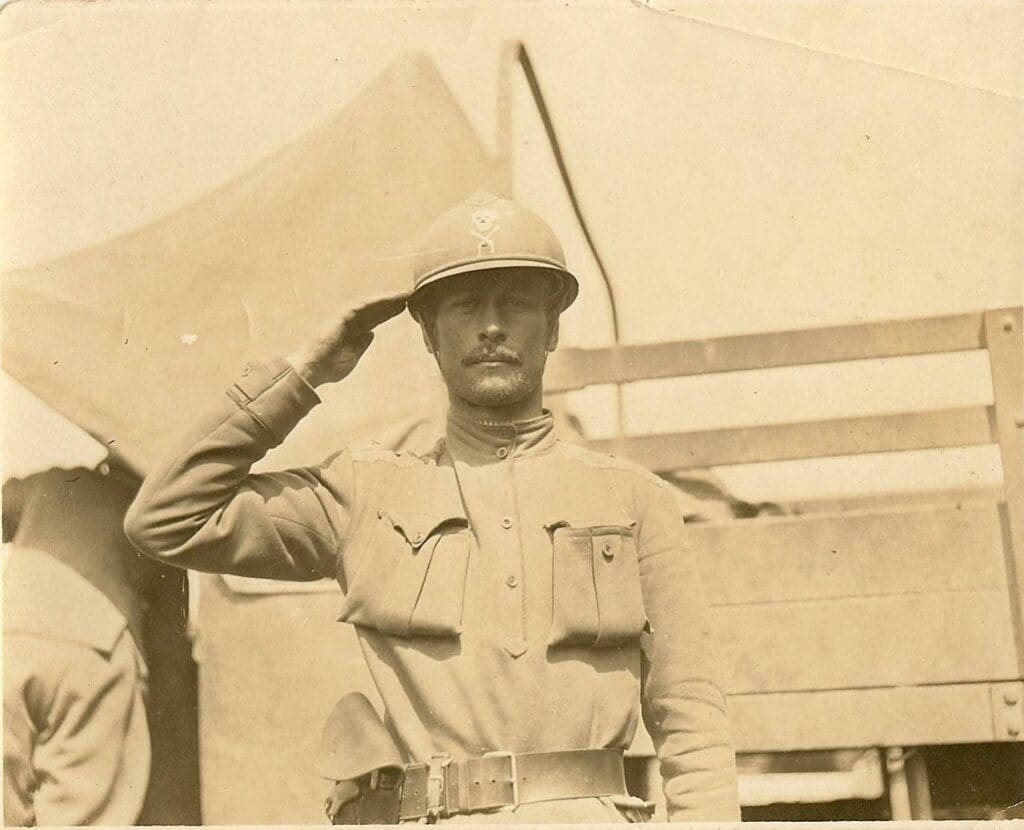

Insignia

One of the distinguishing characterizing of Imperial Russian Adrian helmets is the double headed eagle insignia affixed to the front of the helmet. The double headed eagle is a main element in the coat of arms of the Russian Empire and generally viewed as a symbol of the House of Romanov. The eagle was frequently featured on Russia military equipment of the era and positioned on the front of the helmet would distinguish the wearer as a solider of the Russian Empire. While the first delivery of Adrian helmets arrived with French insignia, a Russian double headed eagle insignia was in the works. The insignia was in fact sketched out by A. Ignatiev himself then submitted to the French helmet factories for manufacture. The insignia would measure 72 mm by 66 mm, made from stamped steel, and painted moutarde to match the helmet color. The insignia were sent in separate boxes from the helmets, and were not attached to the helmets until after arrival in Russia.

Despite the first consignments of helmets being painted horizon blue, no Tsarist insignia were ordered in any other color than the moutarde. Even in the monochrome photos of the era, the contrast between the moutarde Tsarist insignia and the horizon blue helmets can be seen.

There has been some debate about the use of the Tsarist insignia in the later stages of the war. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated his throne in March 15, 1917 after which the reigns of power was put into the hands of a provisional government. It is assumed among some that due to the abdication that the Russian soldiers removed the double headed eagle insignia from their helmets seeing it as symbol of the former régime. While undoubtedly some men did remove the insignia for that very reason, many did not. Photos taken well after the March 15 abdication still show that insignia being worn. Even as late as the Kerensky Offensive in the summer of 1917 when disgust with the Russian provisional government was at epidemic proportions photos, show a good number of men still wearing the old Tsarist insignia.

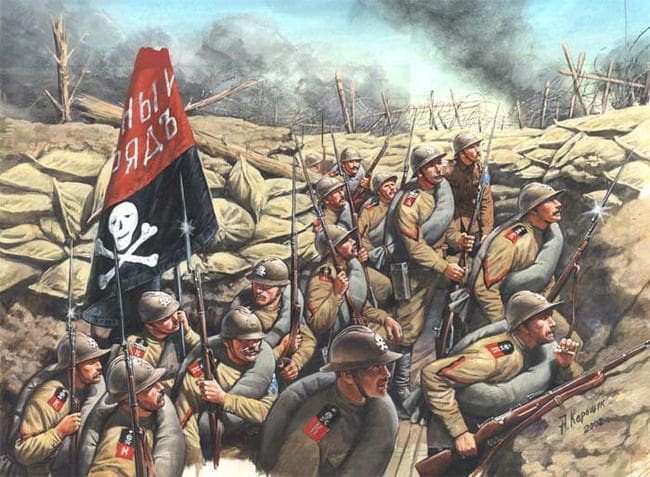

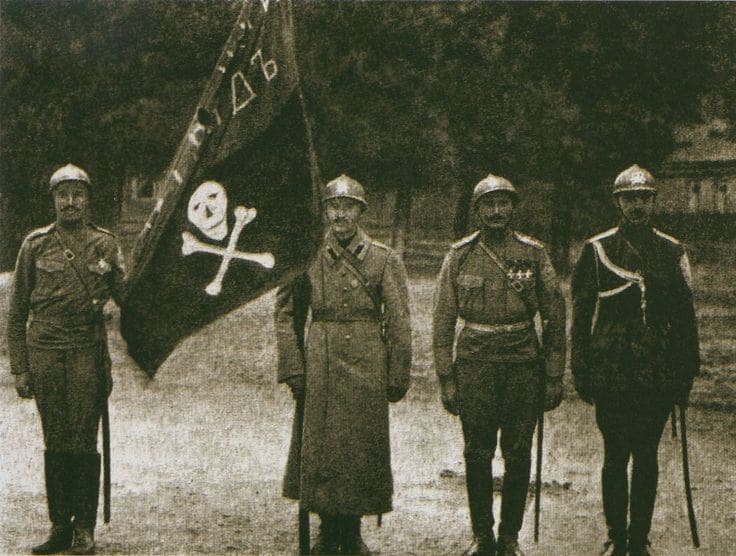

Shock Battalion Death Heads

The last Russia Offensive of the Great War was planned for the summer of 1917. It would be known as the Kerensky Offensive, after Alexander Kerensky, Minister of War. In preparation for this last push, 30 specially trained volunteer units known as Shock Battalions were formed. These units were given the dangerous task of probing and exploiting weak points in the enemy’s defenses. Due to the rather hazardous nature of shock battalion’s work, Russian quartermasters managed to outfit the majority of these troops with helmets. One battalion was made up entirely of women, but photos would indicate they did not receive steel helmets. Owing to the treacherous nature of their task, these units adopted a death head as their insignia. A few of these battalions painted a white skull on the front of their helmets in place of the Tsarist insignia.

One of the more famous of these shock battalions, the so called Kornilov 1st Shock Detachment, would continue to use the death head insignia on their helmets in the subsequent Russian Civil War while fighting in the ranks of the White Army.

Macedonia and France

While Russian troops on the Eastern front may have struggled to obtain a steel helmet, this was not the case everywhere. By agreement with the French government, Russia sent troops to fight under French command in France and on the Macedonian front. As part of the agreement, these Russian troops would continue to wear Russian uniforms but would receive French arms and accoutrements at the expense of the French government. This included Adrian helmets. The Adrian helmet these Russian troops would wear in France and Macedonia did not differ from those worn by their counterparts in the east. When the Russian troops arrived, they were given moutarde colored Adrian helmets with Tsarist insignia on the front. Because these troops were equipped directly from French quartermasters, unlike in the east, these Russian troops all received Adrian helmets; there were no shortages.

Some further discussion is necessary when addressing the helmets worn by the Russian Expeditionary Force in France, (Corps Expéditionnaire Russe en France.) In March 1918 the new Soviet government of Russia signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk formally ending the war between the Central Powers and Russia. Some Russian troops in France still wanted to keep fighting. Those that did were allowed to join a new unit being formed called the Russian Legion which became part of the 1st Mocorrcan Infantry Division. Members of the Russian Legion wore a mixture of French Colonial uniforms and elements of their old Russian uniforms. Some men, for reasons of their own, continued to wear the old Tsarist Imperial Eagle on their helmets while others wore no insignia at all. A few solders received Adrian helmets with North African colonial insignia because the unit was part of a North African division, it was likely the quartermasters made no disinction when issueing new helmets.

Continued Use

With the end of the Great War, the Adrian helmets purchased by the old Imperial régime would continue to see service. When the Russian Civil War broke out, both the Red and White Guards would wear these same Adrian helmets as they battled to control the remains of the Russian Empire. With the Soviet victory, these same helmets continued to be reworked and reused until the eve of the World War II. These helmets also made their way into the military equipment inventories of the various new nations that came into existence with the dissolution of the Russian Empire. The new armies; Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, and Finland, all continued to use the Adrian helmets left over from the Great War.

What Might Have Been

As has been discussed, Russia was slow to see the benefits of a steel helmet. When the Tsar finally did give his blessing to purchase helmets, it was almost too late. The numbers of helmets worn by Russian troops on the Eastern front was not sufficient when compared to almost every other army in the war. With the lives the steel helmets would save, it begs the question what the effect might have been had the entire Imperial Army had a helmet by early 1916. Would the number of lives saved have changed the outcome in the East? It is impossible to say. Large events in history are sometimes the result of small seemingly inconsequential events. Maybe an empire could have been saved by a steel helmet.