Specters in the Snow, the story of Finland’s Skeleton Helmet

A Savage Snow War

On a freezing day in January 1940, near the village of Muurila, a Red Army soldier crept through the snow. He placed himself as close to a tent, as he dared; he knew it contained his Finnish enemy. He lobbed his grenade and waited for the consequences to unfold. This hostile action was a small part of the so-called Winter War. Since November 1939, the Soviet Red Army had been fighting a vicious war of domination with the neighboring country Finland. Inside the tent was Captain Ryandall Nybom, one of the officers leading the Finnish army unit Kevyt Osasto 4. Nybom was conferring with a courier who had been sent to deliver a message. The grenade exploded in close proximity to Nybom, the concussion blew off the side panels of the old Great War era German M16 helmet he was wearing and lodged shrapnel in his shin. Though dazed and wounded Nybom would survive. The old helmet had done its job. Sadly, the courier was not as fortunate. He died moments later in Nybom’s arms as the captain, though badly injured, tried to comfort him in his last moments.

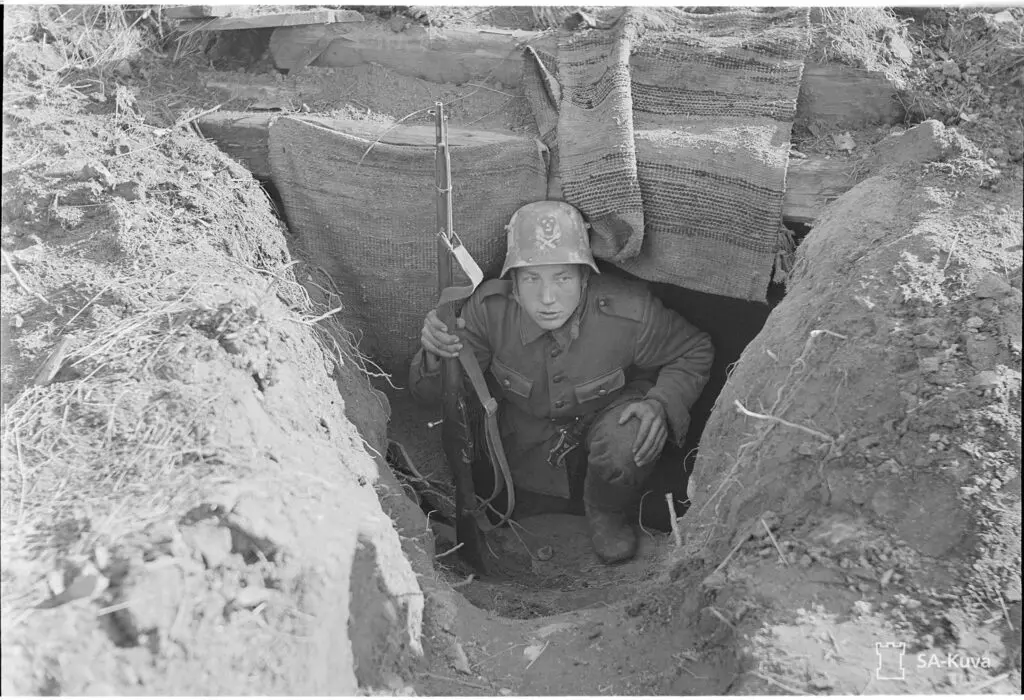

Captain Nybom’s helmet was emblazed with a ghoulish skeleton, hand rendered on the front, in white paint. Along the sides of the helmet were stylized swirls running down both panels emanating from the skeleton’s arms. The fantastic camouflage design was not unique to Nybom, in fact, the pattern was adopted by the entire unit. Today, to some degree, this unique camouflage pattern has become a symbol of the Finnish army during the Winter War.

Of Skulls & Bones

Almost anytime the Winter War is written about or discussed online, more often than not a photo will appear featuring a Finnish soldier wearing a helmet with a skeleton rendered on the front. It would be easy to believe that all Finnish solders wore such a helmet. In truth, the practice was limited almost exclusively to one particular unit. That unit was Kevyt Osasto 4, or in English, Light detachment 4.

The origins of the skull and bones insignia actually pre-date the Winter War. During Finland’s 1918 Civil War the Uusimaa Dragoon Regiment second squadron, would take on the moniker Kuolemaneskadroona or the Death Squadron. This new appellation was given as an honor due to the unit’s bravery and success during combat operations in the battle of Kuhmoinen. With the new name, this company created a symbol for themselves. The skull and crossed bones with the number 2 on a shield. The skull and bones insignia would be emblazed on the company guidon and would be featured on various insignia.

The skull and bones have a long history of use by various militaries world-wide and is by no means confined to Finland. Historically, the symbol represents mortal dangers to all those who choose not to heed its warning. It should come as no surprise that soldiers would embrace the bravado of using such a symbol as a means of intimidating their enemy; a chilling reminder “to confront us is to court deathâ€. The members of Kuolemaneskadroona would have certainly believed they had earned much a message.

Kevyt Osasto 4

Prior to the Winter War, Second Squadron was commanded by Rittmeister Alfons Sundblad. As the Winter War commenced, Sundblad was reassigned to command of Kevyt Osasto 4. It would appear that Sundblad really enjoyed the traditions of his former mounted unit and presented himself as the dashing dragoon officer with all the trappings. In photos from the era, he is usually seen vested in jodhpurs, leather riding boots and a riding crop in his hands. It should come as no surprise that Sundblad would bring some of the traditions he enjoyed from his former unit with him to Kevyt Osasto 4.

Sundblad was not the only officer in Kevyt Osasto 4 to have a connection to a mounted unit. Captain Randall Nybom a company commander, had likewise served as a pre-war cavalry officer. The two men collaborated in creating an unofficial insignia for their new unit, which they borrowed from Kuolemaneskadroona. It was, of course, the skull and bones. Kevyt Osasto 4 was more than just a regular infantry unit. The men would be highly trained to serve as a mobile unit. which meant they were intended to move rapidly to wherever there were emergencies at the front. The skull and bones would have symbolized the deadly tasks the men would be taking on.

Sundblad and Nybom likewise tagged their unit with the nick name: Kuolemankomppania, or the Death Company. It would appear the men embraced the skull as a proper symbol of their unit. In a gesture of respect, the men of Kevyt Osasto 4 presented Nybom with a wooden judge’s gavel fashioned to look like a skull. Nybom had been a lawyer prior to the Winter War and would go on to serve as a judge and later politician.

On the helmet too?

At this point, the men of Kevyt Osasto 4 deciding to camouflage their helmets with the unique skeleton pattern camouflage is lost to history. The earliest appearance of these helmets in photographs is December 1939. In the picture the helmets show evidence of wear, which indicates the camouflage had been applied sometime pervious to the picture being taken. At the time of the photograph, Kevyt Osasto 4 was involved in heavy fighting to repel a Red Army breakthrough on Mannerheim line. Nybom who survived the war and passed in 2003 was interviewed on a number of occasions about his service in the Winter War. It would seem historians never felt the skeleton helmets were of enough significance to inquire about. Others have speculated that an order was issued by Sundblad himself requiring the men to camouflage their helmets in that manor prior to combat. If such an order was given, a record of it has not surfaced in Finnish archives at this time. It should be noted that Sundblad had his helmet camouflaged with this pattern and was photographed wearing it well into the Continuation War. That fact would indicate that he certainly approved of it. The photo of Nybom and his compatriots wearing these camouflaged helmets, is the earliest appearance of the pattern. Instead of being some sort of direct military order, it might have been seen as a clever idea passed by word of mouth to the members of Kevyt Osasto 4.

Within the ranks, there were a few men who painted for a living in their pre-war lives, professional sign painters or a similar profession requiring artistic skill. These men would have been tasked to apply any camouflage patterns that the unit required. They may be the ones who actually created the design after being told what was desired by their superiors. While the patterns do vary somewhat, indicating different artists, they all have a basic form. That of a grinning skull with cartoonishly large eye sockets, mounted above a ribcage. The strangely large eyes were probably influenced by cartoon characters of the 1930s such as the creations from Walt Disney or Max Fleischer studios. Many American animated cartoons were international successes and enjoyed by Finns prior to the war.

Being from a land covered in snow a many months of the year, the Finns were masters of winter camouflage. Understanding the snow-covered terrain of their homeland, they utilized all sorts of white articles of clothing to blend perfectly into the environment. The green-gray painted steel helmets they wore were no exception. The undulating white pattern emanating from the skeleton would have blended well with the white snow and shade of green and brown from the conifer forests of the Finnish countryside. Not only did the skeleton camouflage offer an intimidating visage to the peasant soldiers of the Red Army, but it was also practical in breaking up the outline of the helmet against the snow chocked Finnish countryside.

Finns in German Helmets

Aside from the painted skeletons, one of the first notable things in the photos of Kevyt Osasto 4 is that their helmets are German. While the Finns would eventually produce their own helmets, in the early year after independence the Finns had to make do by procuring foreign helmets. The Imperial German army had assisted Finland with their independence in 1918. After the German troops returned home, some equipment was left behind including the classic horned steel helmet. In the aftermath of the Great War, and Germany’s defeat, their steel helmets were available for purchase by any nation who needed them, and Finland did. In 1919 Finland purchased 15,000 German and Austrian model helmets directly from France where they had been confiscated from the Central Power at the end of the Great War. The helmets were then reissued to Finland’s fledgling armed forces. In the 1930s the Finnish military procured some 80,000 more of these helmets. By the time the Winter War commenced in 1939, most of the Finnish army was wearing German or Austrian helmets of Great War vintage. All models were known to have been utilized by the Finnish army. In examining original photos, Austrian M17s, German M16s, M18s, and M18 ear cut-out helmets can all be seen. These helmets were reconditioned only as needed. Some were repainted with a shade of grass green and others were left with the WWI era factory finish. Liners, chinstrap and pins were replaced when needed with Finnish made versions.

Skulls and the Continuation War

The Winter War ended in March 1940 but there was only brief peace. In 1941, Finland was once again embroiled in war against the Soviet Union. This second war is known in Finland as the Continuation war and more broadly: World War II.

Alfons Sundblad was promoted to the rank of Major and reassigned to a new unit: 1. Pataljoona / Jalkaväkirykmentti 46 or 1/JR46. Sundblad once again brought his love of skulls with him. As with Kevyt Osasto 4, 1/JR46 adopted the skull and bones as their unofficial insignia and took on the moniker Pääkallopataljoona (Skull battalion). Sundblad ordered a few versions of skull and bones insignia to be created. These were pins for his men to wear on their wool caps, and even belt buckles with skulls for the officers serving under him.

Regarding the helmet itself, a new look would be required. The Continuation War broke out in the summer of 1941, the snow camouflage skeleton helmets would have stood out in those conditions. Thus, a new much smaller version was created and rendered onto the helmet. Photos show a few different variants, but none retains the ostentatious appearance of the original worn by Kevyt Osasto 4 during the Winter War.

As to exactly when the skulls start to appear on the helmets of 1/JR46, it can only be guessed. The war time records of 1/JR46 are silent on the matter. A photo of the unit participating in a parade for 75th birthday celebration of C. G. E. Mannerheim in June 1942 show all members wearing these skulls painted to the front of their helmets. It is likely that some sort of order had been issued to assure some consistency.

The skeleton helmet of the Finnish military was never as common as photos circulating the internet and social media would lead one to believe. Yet, due to their unique nature, the men photographed wearing these helmets have become the very symbol of the Finnish soldier in this era. Often when discussion of the Winter War or Continuation war are brought up someone invariable states, “those men were the ones with the skulls on their helmetâ€. Even if that statement is only true in an outsized way, it was done. The Finnish army fought bravely with a tenacity that shocked Stalin’s Red Army. They managed to inflict casualties many times higher than anyone thought possible. Finnish forces would kill well over 126,000 members of the Red Army during to Winter War opposed to losing 25,000 of their own. If the skull and bones is a warning of death, the Finn have earned that honor.