An American Helmet in China, The helmet of the China Marines 1927-1941

U.S. Marines in China

On the 21st of March 1927, Stirling Fessenden, the American chairman of Shanghai’s International Settlement’s Municipal Council, issued a declaration of emergency. Generalissimo Chang Kai Shek’s Nationalist army was marching toward Shanghai. For several years China had been experiencing spasms of violence as the factions of warlords, gangsters, Nationalists, and Communists all attempted to assert their control over the fractured country. That violence had only really affected Chinese citizens; the many foreigners that lived in China remained safe in their enclaves. However, in July 1926 that tenuous détente would change. Generalissimo Chang Kai Shek ordered an expedition by his Nationalist forces to defeat the various warlords of Northern China in the hopes of reuniting China under his rule. During what would be called the Northern Expedition, the Nationalist not only attacked the warlords but also Japanese, American, and European citizens. Their possessions were seized, they were attacked, and there are documented accounts that some of the foreigners were murdered. Nationalist troops even went as far as to seize the British controlled concession in Hankow. As Nationalists approached Shanghai in the winter of 1927, Americans living in the International Settlement had every reason to be nervous about what might happen when Generalissimo’s men arrived at the city gates.

Fessenden had already ordered the Shanghai Volunteer Corps to construct and man various barricades around the International Settlement, but it was unlikely the little force would be able to hold out against determined Nationalist troops. Help would be needed and would come in the form of the U.S. Marines.

American Marines from the 3rd Battalion 4th Regiment had for some time been biding their time aboard the USS Chaumont in the Shanghai estuary. They had been sent to China weeks earlier by the US government due to the deteriorating political situation within the country. When Fessenden’s plea for help was received, the Marines disembarked from their ship and assembled on Shanghai’s famous waterfront the Bund.  From there they marched past the massive Bank of Hong Kong and Shanghai, the internationally renowned Cathy Hotel, and various other foreign consulates and businesses that lined the Bund, all symbol of Western Power in China. The arrival of the U.S. Marines was met with great relief by Shanghai’s international community.

Now that the U.S. Marines had arrived, a clear signal had been sent to both the Chinese and foreign residence in Shanghai, that the International Settlement would be protected. Soon after the Marines arrived at the Bund, Nationalist troops arrived in Shanghai. There was little violence however directed toward Americans and other foreigners living in the International Settlement. Chang Kai Shek and his Nationalist government continued to honor the foreign concessions in Shanghai.

The 4th Marines ended up staying in Shanghai with a few being sent to American outposts in Peking and Tientsin. They served as protective force for American citizens and their property. The Marines in Shanghai eventually gained the moniker China Marines while those Marines in Peking and Tientsin were called North China Marines.

While the threat from the Chinese Nationalist troops turned out to be overblown, China would soon find itself embroiled in a vicious war with the Empire of Japan. As this war started to take shape, the China Marines would be there to man barricades around Shanghai’s International Settlement in an attempt to keep the fighting from spilling over. They performed this duty until November 1941 when the U.S. government redeployed them to the Philippines just weeks before Pearl Harbor. These Marines were the first Americans to witness a war that would soon envelope their own nation.

Helmet of Great War Vintage

The American Marines who arrived on the Bund in March of 1927 looked much the same as their predecessors who fought in France nine years before. They still carried the same 1903 Springfield rifle and wore the same soup dish style helmet. Due to budgetary constraints that were placed on the military in the 1920s, no upgrades were made to the helmet; therefore, the Marines had to make do with aging WWI era helmets. At the time there were two model helmets that were in Marine’s inventory: the British Mark I and the American M17. The British manufactured Mark I helmets had come into U.S. military inventory during WWI at a time when there were not sufficient American made helmets available. As both U.S. M17 helmets and British Mark I helmets looked essentially the same, no distinction was made between the two by the Marine Corps. Both of these helmets were worn in China.

The helmet’s liner was designed to accommodate any head size. The only way to tighten the helmet was by cinching the chinstrap down which did not always do the trick. Corporal Leonard Dombroski, an American Marine who arrived in Shanghai in 1937, had little good to say about his helmet. He would recall, “Yes, I hated the helmets…they were worthless: if you hit the deck, it usually fell off. They told us not to wear the chinstrap under our chin as if there was a near miss the helmet would snap your neck from the concussion. Instead, they taught us to wear the strap behind your head.” Despite Corporal Dombroski’s reluctance to wear the helmet’s chinstrap, photos show many Marines wearing them in China.

Insignia

One of the distinguishing features seen on China Marine helmets is the Eagle, Globe, and Anchor insignia, (EGA for short) affixed to the front. To install these insignia, a hole was punched into the helmet steel, three finger widths from the base where the dome meets the helmet’s skirt. Due to the fact that finger widths vary somewhat, some insignia were placed higher on the dome than others.

It appears from photos that these insignia were not worn with total consistency. Early photos from the late 1920s show an inconsistent mixture of detachable metal EGAs, painted EGA applied by means of a stencil, or in some cases no EGA at all. By the mid 1930s, photos of the detachable metal EGAs were also standard, but black painted EGAs continue to surface in photos as late as 1937.

There are several different variations of EGAs that were worn by Marines during this era. The most commonly worn EGA in China was the so called “standing eagle” EGA. This design was adopted in 1925 but isn’t seen in large numbers until the 1930s. The prior design used during WWI and immediately after, is often referred to by collectors as a “sitting eagle” EGA. Both types of insignia were worn.

There were a number of different manufactures of EGA insignia and small variations exist between the makers. These small variations can lead to confusion among collectors about which insignias were worn at certainly times and have given rise to a few collector myths. One such myth is that the China Marines had their very own EGA made specifically for them. Like many myths this one has some basis in fact. During this era Shanghai was home to a number of excellent jewelers. Aside from highly skilled Chinese craftsmen there were also world-class White Russians and Jewish jewelers who had fled persecution in Europe and set up shop in the International Settlement in Shanghai. A very small number of EGAs have surfaced over the years with Chinese characters stamped on the back that have China Marine or North China Marine providence. These EGAs vary from fine quality to crude craftsmanship. Due to their rarity, little is known about these EGAs and how many were actually made. It is very possible that China Marine quartermasters contracted with local Shanghai jewelers to make a few orders of EGAs to cover shortfalls in their supplies. It also likely that a few men and officers wishing to have a higher quality EGA went to a local jeweler to have one made to their liking. What is known is that at least a few unique Chinese made EGAs exist and are unique to the China Marines.

Paint

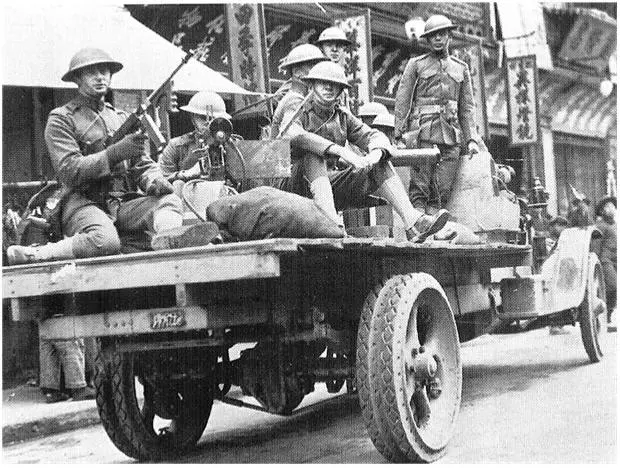

An unusual feature often observed in photos of China Marines is the glossy finish on their helmets. This practice can be seen on helmets of both the China Marines in Shanghai as well as the North China Marines in Tientsin and Peking. Early photos taken of the 4th Marines in the late 1920s show helmets with the same matte sawdust or gravel textured finish worn by their predecessors during the Great War. Sometime after this, these helmets were stripped of the matte textured paint and refinished with a glossy coat of olive colored paint. The high gloss finish observed in many photos indicates that the Marines polished their helmets to achieve an even higher gloss. Some China Marines would hiring local servants to wash and clean their uniforms and accoutrements. It is almost certain that these servants polished the helmets as well.

It would seem that these showy helmets were only appropriate for the parade ground and Embassy or ligation guard duty, but photos show this was not the case. In 1932 and later in 1937 Chinese Nationalist Troops would clash with Japanese Empire troops over the control of Shanghai. During both of these incidents, the boarders of the International concessions were respected by both sides, but at the time there was the very real possibility that the fighting would spill into the International Settlement. On both occasions the Marines were called to man barricades around the settlement boarders, most notable at Soochow Creek and the Sinza Bridge. Despite the very real possibility that these Marines would be taking fire from the Japanese, photos taken during both these occasions show both glossy helmets as well matte finish helmets being worn.

The M1917-A1 Kelly Transitional helmet

The second battle for Shanghai in 1937 between the Chinese and Japanese would turn out to be much bigger than the 1932 incident. It was feared that the 4th Marines would not have the manpower to hold off the Japanese should they attempt to penetrate the American sector of the International Settlement. Reinforcements would be needed, and the 2nd Marine Brigade was sent to Shanghai to bolster the 4th Marines.

Members of the 2nd Marine Brigade came equipped with upgraded M1917 helmets known as M1917-A1 Kelly helmets. These reworked Kelly helmets had been authorized since January of 1936 but replacing the old M17s was done very slowly. These helmet had a new liner system with an aluminum frame which could be adjusted for the wearer’s comfort. An adjustable web chinstrap with a brass clasp completed the package. The helmets were painted with a shade of matte olive drab paint textured with crushed cork, sawdust, gravel, or pulverized walnut shells.

During the 1937 battle for Shanghai, the reinforcements that arrived to bolster the 4th Marines were wearing these Kelly helmets. The 4th Marines apparently received a shipment of Kelly helmets around this time as well, as they started appearing in photos taken during this time. While photos of the 1932 incident show many if not most of the Marines wearing glossy helmets, by 1937 few glossy helmets are seen. At this point most of the photos show the Marines regardless of unit wearing the new Kelly helmet.

What happened to the Helmets?

China Marine helmets with proven provenience are rarely encountered today. Few collections can boast of a legitimate example. At the writing of this piece even the National Museum of the Marine Corps lacks one of these helmets in their extensive uniform and helmet collection. Part of the reasons for this is the helmets rarely left China. When a China Marine returned home or was reassigned, his helmet was turn back in to be reissued to Marines in that unit. The other more tragic reason has as much to do with the fate of the China Marines themselves. With the Chinese defeat at Shanghai in 1937, the Americans realized it was only a matter of time before the Japanese made a claim on the International Settlement, and U.S. policy makers knew the China Marines didn’t have the resources to hold off the Japanese for long. Believing that war with Japan was imminent, the withdrawal of the China and North China Marines to the Philippines was ordered beginning November 10, 1941 by the U.S. government. A small stay behind force was left to guard the Embassy in Tientsin, the Legations in Peking and Consulate in Shanghai.

Due to the hasty withdrawal, a lot of equipment including helmets were left behind. Much of it was likely scraped after the Japanese overran the International Settlement in December 1941. The China Marines who had watched from the sidelines as the Chinese army clashed with the troops of the Empire of Japan in the streets of Shanghai soon found themselves fighting that same enemy. After Pearl Harbor marked the entry of the U.S. into World War II, the Philippines were attacked and soon overrun by the Japanese military. The members of the China Marines who survived to surrender were marched into hellish Japanese POW camps where they would languish under horrid conditions until the end of the war. Many did not survive. The helmets they had worn in China and the Philippines were discarded and ended up as scrap. Because of these situations, there was little opportunity for the helmets to find their way into modern collections making them extremely rare and highly sought after by collectors.

A Helmet with Legacy

The China Marines are a small footnote in the history of the U.S. involvement in WWII. The helmets these Marines wore may not be easily recognized by the average person as a symbol of WWII like the M1 pot, but still the China Marine helmets should be given some consideration. The China Marines in their soup dish helmets were the very first Americans to face enemy troops from the Empire of Japan. While no major confrontations between the two sides happened, the possibility was always there and those China Marines no doubt realized that sooner or later they would be fighting the Japanese. This would make the China Marine’s helmet the very first American helmet of WWII, and it deserves it’s place in the history of that war.